Calling Grandma

It is hard to put in words how I feel about this piece. I was given the gift of telling my Grandmother’s history and our relationship for The New York Review of Books. This is a deeply personal story about love, struggle, precarity, Mizrahi life in America and survival. You can also hear a reading I did of the piece below.

When I was seven, Syd was my best friend.

Hers was the first number I memorized when I learned to use a telephone. She would answer, a little curious and with a Brooklyn air of “Who the hell is this?”, which gingered up as soon as she heard me say “Hi, Grandma.”

I’d call every day when I got home from my North Hollywood elementary school. Whenever I felt a sharp pain in my ribs, or just generally off, I went into our butter-yellow kitchen and dialed. “It’s gas,” she usually said, in a raspy pack-and-a-half timbre. After moving from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, Syd had enrolled in a program that trained low-income women to become nurses. She practiced until her early sixties, mostly in convalescent homes where she called her patients “my babies.” After she retired, she became the family’s Florence Nightingale. I was her most demanding patient.

Once she’d dispensed her quickfire diagnoses, we’d speak about school—what I was studying, and the boys, especially the one I loved, the blue-eyed, black-haired boy, who relentlessly teased me. She referred to him as “the womanizer” until she heard he’d punched me in the stomach for trying to kiss him beneath the school’s oversized eucalyptus tree; then he became “the asshole.”

Sometimes on our calls her voice had a swish to it, with gurgled R’s and fuzzy S’s that hissed like a record player. These conversations were also more tender. She addressed me rouhi in her native Arabic, her “soul,” and told me sternly, “Don’t you dare tell your cousins, but” her words suddenly syrupy and curing, “of all the grandchildren, you’re my favorite.”

Through seventh grade I was flat-chested and fifteen pounds lighter than most of my classmates. I was anxious about puberty and called her constantly to ask why it had come on for everyone except me. Over the sound of The Price Is Right playing on TV, she’d yell, “There’s nothing wrong with you!” When finally my body started to morph and the “mosquito bites,” as the boy called them, appeared on my chest, I called Syd. “You see? What did I tell you?” She took me that week to May Company on Wilshire Boulevard to pick out my first preteen bra: a pale pink jersey cup filigreed with white lace.

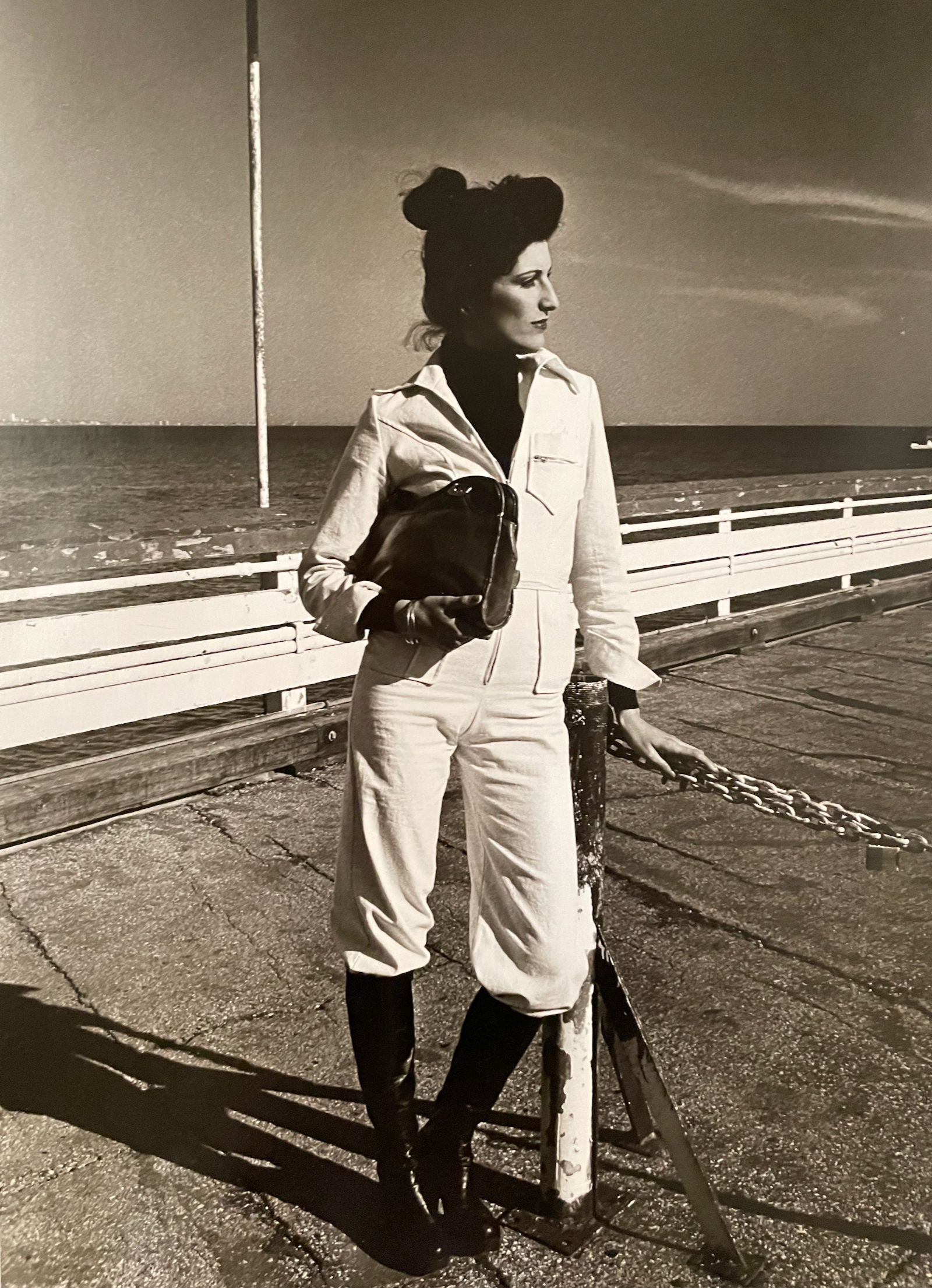

Syd always looked like a 1950s movie star, long slim legs in her pastel cotton pants, thick leather belts cinched tight around blousy cotton collared shirts. She tucked her faux alligator-skin pocketbook, the size of a large envelope, under her arm or let it dangle from her self-manicured hands. And always two packs of Virginia Slims tucked inside.

In eighth grade, a deeper self-consciousness set in: I worried that I sweat too much, and I wouldn’t finish sentences for fear I was saying something wrong. The boy, of course, pounced on my awkwardness and started to call me La-Risa, “Lame-plus-Marisa,” as he explained it. He would shout it out as I took my books out of my locker. Soon, the whole school had adopted the moniker. At bar mitzvahs, I would get pulled to the dance floor with an eyeroll and a muttered “La-Risa, wanna dance?”, usually about half a minute after a song had already started.

But with Syd, I was the world. Whatever problems I brought to her were either manageable or nonexistent. “Screw ’em. What do they know? You’re gorgeous,” she told me.

Her childhood and mine could not have been more different. For a time, back in the 1920s, her family had been homeless in New York. Her father had contracted tuberculosis, and left for California when Syd was still a baby because the family thought the climate might help him; he died there soon after. Later, the fatherless family lived in a tenement on the Lower East Side, at a time when earlier Jewish immigrants were already moving out to relative prosperity in the Bronx suburbs. On the days they had no food to eat, her mother would make a show of cooking by boiling water on the stove, so that the neighbors, seeing steam in the kitchen, wouldn’t know they were going hungry.

Syd’s mother remarried a cousin when she was a toddler, and the family moved, as most other Syrian Jews were then doing, to Brooklyn. Syd had to fight to graduate from high school. All the same, she was in her early twenties when she married my grandfather. Joe, known as “Lang,” was another Syrian Jew, an unheard-of six-foot-two, with pale blue eyes and a shock of black hair. He was obsessed with everything about Syd’s appearance: her legs, charcoal curls, pillow lips, and toothsome smile. The two had a reputation in the community as bitjanen, or “beautiful”—they belonged in Hollywood, everyone said, not Bensonhurst.

Then children arrived, the first three in swift succession. After a five-year break my mom arrived. But cracks had started to appear in their marriage. In truth, Syd had never wanted to marry Joe; if she had had her way, she would have settled down with the man she had fallen in love with—a ja-dub (Arabic slang for Ashkenazi), no less—before my grandfather entered the picture. Such a match was looked down upon in the community—but then so was divorce, and that didn’t stop Syd.

Though crushed by it, Joe finally relented. And so, in the late 1950s, when my mom turned eight, her parents sidestepped the traditional Jewish get and paid a ten dollar fee to certify their divorce by mail, citing “incompatibility of temperaments,” from a court in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Joe left Brooklyn and found work in New Orleans.

Back in New York, Syd started working, too—something that barely any women in the Syrian community did then. At one point, she was running two costume jewelry stores on Bay Parkway and Avenue U, but the pressure of being in business drove her to a nervous breakdown that left her passed out on the floor of one of her stores. Syd lacked support or guidance from family or community, so it fell to her eldest daughter—just eighteen at the time—to check her into Bellevue, where she spent several weeks recuperating.

In the early 1970s, Syd took my mother out of high school and moved to Los Angeles to be there for the birth of my aunt’s baby, Syd’s first grandchild. Missing Brooklyn, my mother hated everything about California: blond hair, surfers, cars. But Syd adored it. She loved how apartment buildings had pools and there were cloudless skies year round. She sunbathed with baby oil and cut her thick undulating black hair just above her shoulders and dyed it blond.

A few years into her California life, my grandfather moved to an apartment building less than a mile from Syd’s, also to be near his grandchildren. He started to work the local swap meets selling Kennington shirts and pantyhose.

After graduating from high school, my mother transformed into a Syrian beauty queen. Her long, tousled hair, aquiline nose, and deep brown, almond-shaped eyes won her first modeling contracts and then a coveted spot as a Playboy Bunny, working as a cocktail waitress in one of Hugh Hefner’s clubs where her confreres called her “the Kosher Bunny.”

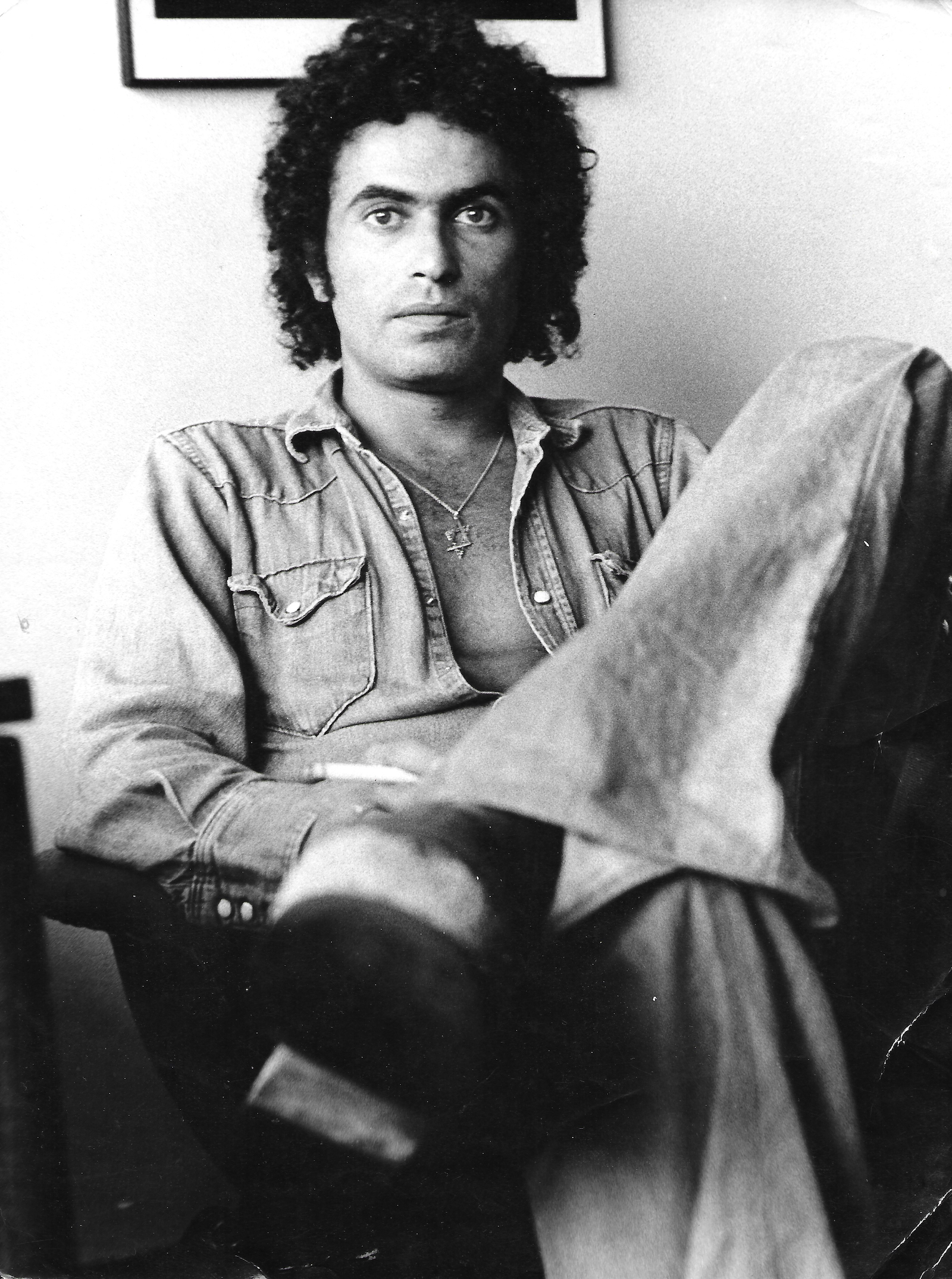

My mother, then twenty-one, first spotted the man who would become my father walking through the Farmers Market, shirtless in denim overalls and yellow clogs. Swinging from his neck was a thick rope of gold with a Jewish star, for he was that then glamorous, romantic being: an Israeli. Their first conversation took place late one night on the dance floor of The Candy Store nightclub in Beverly Hills. After dating for less than a month, they took a “champagne flight” to Vegas and eloped.

My grandmother hated my father at first for his machismo. Together with my mother, my father started a business out of the basement of their apartment building just off Fairfax Avenue: it was an office supply company that had no supplies. When a customer wanted some item, my father ordered it from a catalog, collected it, and completed the sale. Slowly, Syd warmed to my father, as she came to admire what a “Jew hustler” he was.

My father thought a pregnant saleswoman could never be turned away. So, the month before my mother gave birth to me, she toted their catalog up and down Sunset Boulevard, knocking on office doors and announcing their new business. The move worked, and eventually they made enough money to get off food stamps, buy real inventory, and rent a storefront in between Wittner’s Cigars and a yarn store. It was right across the street from the Farmers Market.

Their business was in full swing by the time they bought a peach stucco house in North Hollywood. It had a kidney bean–shaped swimming pool in the cement-slab backyard. The house was flanked with fancy flagstone walls, but it also butted up against the back of an apartment building, whose residents could see right into our home.

Syd would come over for dinner every Sunday from as early as I can remember. Around the age of five, I started staging mini-musicals for her. I made the grown-ups my audience as I performed songs like “Le Jazz Hot” from Victor/Victoria and “I Hope I Get It” from A Chorus Line. Each carried a feeling of New York, or of some bustling city of skyscrapers, where, in my mind, I imagined Syd belonged. Even though Syd had moved from New York some fifteen years earlier, she talked about it as if she’d never left.

Sometimes, Syd would put on a cassette tape of Port Said, a collection of Egyptian music from the 1950s. She would sit, a half-smoked cigarette hanging from her lips and her gold bracelets clanking, as she showed me how to twist my wrist, shake my shoulders, and later, when I was around seven, how to move my hips and swing my legs. Even with my Ashkenazi complexion and straight, golden brown hair, the way I moved convinced her I was Syrian, or as she put it, “a real S.Y.”

Although he was Israeli, my father had actually been born in a displaced persons camp outside Munich, Germany, amid the ruins of Europe at the end of World War II. His parents had lost countless relatives in the Holocaust. On the boat to Israel, his father, my grandfather, Moshe, suffered a heart attack and nearly died—he spent the rest of his life needing frequent spells of bed rest. Thus even this new chapter of their lives in Israel carried a sense of blight. My father learned only at his father’s funeral that Moshe had had a previous wife and two daughters who’d died in a concentration camp.

It all left its mark on my father. My Aba didn’t resemble any of the other kids’ parents in California. His accent was thick, and he had no patience for American decorum. Some classmates called him Gaddafi, because they thought he looked like the Libyan dictator, when he picked me up from school. One time, he showed up to a bat mitzvah party at the Beverly Hills Hotel in running shorts and, visibly, no underwear—a habit of “going commando” he’d acquired when stationed in the Sinai Desert during the 1967 war—and started munching on the kids’ chocolate candy he picked up off a table.

If he was frustrated, if something wasn’t going the way he wanted, he would yell and scream. His outbursts of rage terrorized me and my younger sister. My mother was powerless to stop them. When I needed an anchor amid our tumultuous home life, I called my grandmother.

When I was in sixth grade, we moved deeper into the valley, to Tarzana. There, I got my own room and a private telephone line. Then my daily chat with Syd went uninterrupted. Every call ended with my telling her, “I love you,” and her responding, “I love you more.”

When I turned thirteen, it was my turn for a bat mitzvah. My father said that girls in Israel rarely had them, so if I wanted to skip the Torah reading and just have a party, that was fine with him. I did, and went for what I thought was a Santa Fe theme: everything was peach and turquoise, and we bought papier-mâché cactuses and coyotes as decoration.

It was the day after the party that my mother intercepted one of my calls with grandma. She picked up another receiver and told Syd that she needed me. Then she hung up and took me to the living room. Now that I was of age, she wanted me to know.

“Grandma drinks,” she said. “She likes her vodka. And I am telling you this because it’s bad. It was bad. When I was a kid, I used to find her passed out on the floor at night.”

Syd’s drinking was what had precipitated her divorce, she said—that, and her cheating on grandpa Joe—and it had led to the family’s breakup. After my mother’s sister and her two brothers left home, she was left alone to deal with Syd’s addiction. She was basically a functioning alcoholic, Mom said, sober during the workweek and drunk on the weekend. She had even showed up inebriated at my parent’s wedding— actually their second one, after Vegas—“the Jewish one,” my mother called it, which took place in the Sinai Temple on Wilshire Boulevard. My mother had repeatedly talked to Syd about her drinking problem, but Syd denied it was even a thing.

Why was she telling me this now? The unadulterated joy of our relationship could have continued. Maybe she wanted me to know that Syd, whom I idolized for her bottomless chutzpah, wasn’t perfect, and that love—for her or anyone else—shouldn’t be predicated on flawlessness.

After my mother told me, I noticed the difference between our normal conversations and the boozy ones. Mostly that the boozy ones were more affectionate. As the years went by and I advanced into my teens, there were times when I didn’t cut off the calls even though I knew she was drunk. I craved the attention from her too much.

“Rouhi,” she’d purr, “rouhi yamama, you know you are my favorite.” These words, sloshed like ice cubes in her mouth, still made the rest of the world dissolve.

In the early 1990s, Syd won a housing lottery and got an apartment for low-income seniors in West Hollywood. This marked a new beginning for her. The building was on a well-maintained block that hung terrariums from lampposts; she’d never lived anywhere so kempt.

My mother and my aunt threw out all her secondhand furniture and bought everything new: puffy white couches and bathroom linens all in matching royal blue. The floors were mustard-yellow shag pile, and the kitchen was neatly finished with wooden cabinets and a dishwasher, the first she’d ever had. The apartment had a small balcony that overlooked the street, with a café table and a chair, so she could sit outside to smoke. She hung potted succulents from hooks, and giant planters on the balcony overflowed with viburnum. Below was a parking garage with a spot reserved for her yellow cabriolet.

At my insistence, because it seemed so magical to me that a caller would hear your recorded voice speaking to them, Syd got an answering machine, even though she was home most of the time. She took great care to create her outgoing message. The phone would ring three times and then Billy Eckstine would sing “Tenderly”: “The evening breeze, caressed the trees, tenderly.” As Syd recorded it, she lowered the volume to say: “Hello. You’ve reached 854—. I can’t take your call right now, so leave a message.” She turned the music back up for a few seconds before the beep.

When I turned fifteen, Syd was diagnosed with lung cancer. She was sure she could “beat it” and had no patience for histrionics. When the chemo made her hair fall out, she took to wearing white canvas hats with pink rhinestones. She kept painting her nails and always wore lipstick. She counted on her survival all of those years to mean that this, too, was something she could withstand and eliminate.

I believed her, of course. So when she needed a wheelchair, I saw it as a minor setback, not an indication of terminal prognosis. When she stopped walking altogether and needed to exchange her couch for a hospital bed in the home and a nurse to help her throughout the day, I thought it was a step taken out of precaution rather than need.

By then I had gotten my driver’s license and could drive over to see her. I would stop by Gelson’s on my way and pick up a huge slice of lemon cake, which she liked to call “half an ass.” I sat at the edge of the bed as she ate. Her appetite had waned, and her curves were disappearing, but she made an exception for this dessert.

One day, I called to tell her I had won a place at Carnegie Mellon University for a precollege program to study acting. She’d never heard of the school, but she saw any kind of university acceptance as a sign of success. She wanted to see me to congratulate me. So, that weekend, I went over. She was now fully bedridden. I climbed in next to her, draped my arm over her chest and put my head on her pillow. We watched some TV, and I didn’t let go until the nurse came by to bathe her. I kissed her goodbye.

A month passed, and I hadn’t gone to see her. By then I knew that she was deteriorating every day; I couldn’t bring myself to see it. But my mother urged me to take time out of school to visit her. She realized that it was just a matter of days for Syd, and that if I didn’t go, I would regret it.

I pulled into her parking lot, walking by her cabriolet, its yellow paint now covered with a thick layer of dust. Inside was just as she had left it the last time she’d been up on her feet and able to use it: there were cigarette packs unopened in the console, the seats still had their lambswool covers, and a Royal Pine air freshener hung on the rearview mirror.

As I came in, the nurse was nudging Syd onto her side in order to straighten up the bed. Syd howled in pain. The sounds were like nothing I had ever heard. When she was done, the nurse beckoned me over. Syd’s mouth was agape, her eyes stared at the ceiling, her skin sunken between her cheekbones and around her eyes. I wasn’t sure if she was aware I was standing there. All the fight in her seemed gone.

I grabbed her hand, squeezed it, and told her I was there. I pulled up a chair and sat next to her. For the first time, I found I had nothing to tell her. After an hour, I had to go back to school. I leaned across her body and said, softly, “I love you.” And her eyes still didn’t move, but as she weakly exhaled, I heard the words “I love you more.”

Five days later, my parents went over to her house. Hours went by and no word. I decided to call Syd’s home myself. My father answered the phone.

“Aba, what’s going on?”

Before he could answer, I heard a noise and then my mother wail.

“Aba?”

“She just died, Marisa. I’ll call you back.”

In keeping with Jewish custom, Syd was buried the next day in an old cemetery near downtown Los Angeles—the very same one where her father had been laid to rest, some seventy years before. The service was in a dim room, thin linen curtains over black steel bars on the windows. The casket seemed crude, no veneer, just sheets of plywood. It was nothing like funerals in the movies.

That evening, I felt like I was floating. The person who had cocooned me with assurances, told me I was strong enough, had been yanked from my life. Though I’d known it was coming for months, there was something brand new about this rawness. I wanted her voice—intoxicated, sober—with me always.

And so I did what I had always done when I needed Syd. I picked up the phone and dialed her number. After three rings, her machine answered, then the message, in her old voice, and finally, those song lyrics: “I can’t forget how two hearts met breathlessly. Your arms opened wide and closed me inside.”