Afghanistan’s Buried Treasure

On the day I visited the site, Osama bin Laden was assassinated. We got word via text message from an Afghan colleague back in Kabul. At one time, it was rumored that the Mes Aynak site was home to an al-Qaeda training camp, abandoned in the late 1990’s after receiving permission from the Taliban to officially establish operations in nearby Kandahar. In spite of all this, we had an incredible experience exploring the area's rich cultural heritage.

Photography by Leon Chew

For 1,500 years, the sandstone cliffs of Afghanistan’s Bamiyan valley encased two towering Buddhas peering sleepily from their caves onto patches of magnolia trees. Nearly 11 years ago, however, the statues were destroyed by tanks, explosives and antiaircraft weapons on the orders of the Taliban government, which condemned the Buddhas as “idols.” So if you flew into the smog-filled skies of Kabul today, interested in looking for one of the country’s most important Buddhist sites, you’d have to head 25 miles southeast, where you’d find yourself at Mes Aynak, on the edge of the tiny but strategically located Logar province.

Mes Aynak is a sprawling, mountainous, 9,800-acre site studded with artifacts that archaeologists believe are as significant as the Bamiyan Buddhas, as well as the remains of civilizations that stretch back to the time of Alexander the Great. It is also, coincidentally, a copper mine—in fact, it’s the site of the second-largest copper deposit in the world. Mes Aynak is one of dozens of known sites across Afghanistan brimming with rich deposits of other minerals—iron ore, lithium and cobalt.

Art is the one thing that gives the message to people outside that we are not just fighters and terrorists.

Not surprisingly, the Afghanistan government is determined to cash in, especially since the United States plans to pull out most of its combat troops by the end of 2014 and reduce accompanying aid in the coming years. Afghanistan has struck an estimated $3 billion deal with the China Metallurgical Group Corporation, a Chinese government–owned company, to mine the copper deposit within the next 30 years. While this certainly could be a jackpot for the poverty-stricken country, it could also come at the price of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage.

The Chinese beat out bidders from Australia and India to win the project, but with a stipulation that mining would not begin until 2014, so archaeologists could dig. The Chinese provided infrastructure and equipment for the excavation, for which the World Bank and the American Embassy, among others, kicked in around $10 million of the estimated $28 million budget. The Chinese have installed an impressive concrete-and-barbed-wire fence along the perimeter, and the Afghan police have provided a brigade of 1,600 guards to protect the copper. For years the site has been plagued by vandals who have chopped body parts off of countless statues to sell on the black market. “The black side of this country is drugs and war, but another Afghanistan, where suffering isn’t the story, could exist,” says Philippe Marquis, the director of the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), who has been leading the excavation to extract as many treasures as possible before the drilling begins.

On the day that I visit, Marquis and his team—which at any given time can include up to 30 trained archaeologists, 50 university students and 150 workers—face a new obstacle: The excavation has been temporarily halted because of some administrative snafu in the Afghan government. Although Marquis is careful not to show his angst, every day that passes means less time to excavate.

We walk up a flight of stairs chiseled into the cheek of a dusty hillside where white tarps enshroud a city of relics, including grand terra-cotta structures used for worshipping, a corridor leading to a small chapel with a seated Buddha, and fragments of faded red frescoes (although most have been removed by the archaeologists, others have been ravaged by looters). Beyond that, more corridors and Buddhas, some with legs crossed, wrapped in what looks like billowy linens. Narrow lookouts carved into cappuccino-colored, baked-brick walls skirt the edges of the monastery. “Preferably, a dig of this nature would remain in situ,” Marquis says. “But because of the proximity to the future mine, everything that can be removed must go. Eventually this entire area will become a huge copper pit.”

It’s a daunting task—the treasures are spread out over nearly 100 acres, and the clock is ticking—but Marquis is optimistic his team can complete the excavation in time. “Considering the damage done by the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, Mes Aynak could be a chance for redemption,” explains Marquis. “It’s an opportunity for the Afghans to take control of their cultural heritage.”

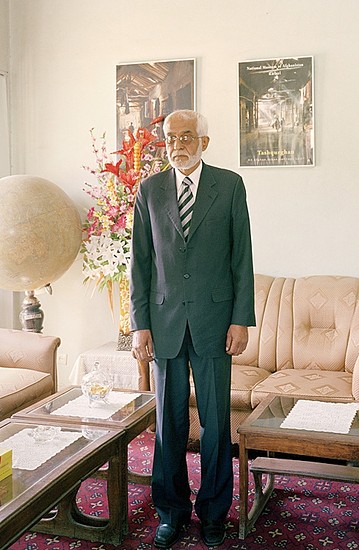

Back in Kabul, Omar Sultan, an archaeologist who is now deputy minister of culture and heritage in the Ministry of Information and Culture, is banking on Marquis’s success. “Just like the minerals, only 10 percent of Afghans’ cultural heritage is out of the earth,” says Sultan, sitting in his cavernous office, in a building tucked behind a towering concrete wall wrapped in barbed wire in the center of the capital. “And with the help of these minerals, we are going to save our cultural heritage.”

Until 1978 a major source of Afghanistan’s income was tourism, explains Sultan. Back then visitors included mountain climbers lured by treks across Noshaq, the country’s highest peak, and sightseers seeking out the ancient shrines and archaeological sites of the Balkh province. Security and a potentially viable cultural infrastructure have Sultan thinking there’s a chance tourists may one day come back. “If, God willing, this country is going to stand up on its own two feet, it is going to be because of tourism,” he says.

Critics at home and abroad continue to fire accusations of corruption and incompetence at the Karzai government. The former minister of mines, Mohammad Ibrahim Adel, for instance, was accused of receiving roughly $30 million in bribes from the Chinese to win the Mes Aynak bid. (Adel stepped down but has denied the allegations.) But the preservation of cultural heritage isn’t just rhetoric. The progress here in the Logar province is evidence of its importance to those who are trying to rebuild Afghanistan.

“The best thing about the Mes Aynak mining operation is the link between commercial activity and protecting cultural resources,” says Michael Stanley, a mining specialist for the World Bank. Stanley believes that Mes Aynak could establish a model in which each new mine containing antiquities would be accompanied by archaeological surveys and cultural investments in the surrounding areas.

Indeed, the Ministry of Information and Culture is spearheading the creation of a new museum in the heart of Logar to house artifacts from Mes Aynak—a much needed project, since the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul cannot handle the scale of the excavation. At one time the museum, located on the outskirts of town, facing a charred former king’s palace, contained some of the most important finds in Central Asia, including ivory from India, bronze from the Roman Empire, and lacquer from China—all recovered from the time when the region was a vital transport stop along the Silk Road.

During the country’s civil war in the 1990s, however, the museum lost more than 70 percent of its collection to looting and bombings. The gray stucco building was abandoned for years until the fighting subsided. Fresh coats of paint have erased the blemished and puffy traces of years of water damage. Stunning relics, like the clay head of a goddess from the fifth century A.D., sit under loosely hung track lights in rooms without guards. One main gallery displays a new exhibition—some early findings from Mes Aynak.

Here, modest glass cases enclose one of the world’s oldest seated wooden Buddhas and four torsos from as early as the third century, each missing their heads due to looters. Although the U.S. has pledged $5 million to resuscitate the museum, and an extra $1 million for partnering with an American institution to train employees, the conditions here are still precarious, with no heating and cooling system in place and only eight conservators on staff.

The office of the museum’s president, Omara Khan Massoudi, overlooks armed guards standing below budding cherry blossom trees. “Art is our responsibility,” says Massoudi. “It is the one thing that gives the message to people outside who only hear about killings and bombings that we are not just fighters and terrorists.” As he speaks, he snakes tasbih, Islamic prayer beads, around his fingers. “And all of these monuments, including Mes Aynak, are the bridges. Every antiquity has a voice of its own that can help send these messages.”

Massoudi’s sentiment is felt most sharply on the campus of Kabul University, where pine and fir trees shade boxy, Bauhaus-inspired structures. Students in traditional dress mix with those in acid-washed jeans and collared shirts. All of the young women have their heads covered, but some of them bare strands of bangs. In one mustard-yellow and rust-colored building, a group of archaeology students have gathered to discuss past trips to Mes Aynak and their hopes of one day returning. The possibility that more archaeological sites will appear in the near future has resulted in exponentially growing class sizes in the past couple of years. But as Ahmad Zia Haidari, a junior, explains, the decision to study in the department was not just about the sector’s potential economic benefits. “I had many chances to choose other professions, but it was the deep emotional connection I got when visiting archaeological sites that made me know it was right,” he says. At 21, Haidari has only ever known Afghanistan in a state of war. “I looked down, saw the relics and knew,” he says, pausing to glance at the other students. “The only way we are going to show the world how strong and powerful we were and could be is through our culture.”